The Beauty

and Spirituality

of the Traditional Latin Mass

by David Joyce

(The

Holy Mass as referred to in this essay is the traditional Latin Mass of the

ancient Roman rite, as celebrated until 1965 in the Latin Church)

It is

the Mass that Cardinal Newman, the leader of the Oxford movement into the

Church, said that he could attend forever, and not be tired. Father Faber,

priest of the Brompton Oratory in the last century, described the Mass as the

"most beautiful thing this side of heaven", and he continued:

It came forth out of the grand mind of the Church, and lifted us out

of earth and out of self, and wrapped us round in a cloud of mystical sweetness

and the sublimities of a more than angelic liturgy, and purified us almost

without ourselves, and charmed us with the celestial charming, so that our very

senses seemed to find vision, hearing, fragrance, taste, and touch beyond what

earth can give.

Father Adrian Fortescue, a great English

liturgical historian, has said that the Mass of the Roman rite is the most

venerable rite in Christendom.

Pious Popes, too, have often wondered at

the majesty of the Mass. Pope Clement VII said in 1604:

Since the Most Holy Sacrament of the Eucharist by means of which

Christ Our Lord has made us partakers of His sacred Body, and ordained to stay

with us unto the consummation of the world, is the greatest of all the

Sacraments, and it is accomplished in the Holy Mass and offered to God the

Father for the sins of the people, it is highly fitting that we who are in one

body which is the Church, and who share of the one Body of Christ, would use in

this ineffable and awe- inspiring Sacrifice the same manner of celebration and

the same ceremonial observance and rite.

and Pope Urban VII in

1634 said:

If there is anything divine among man's possessions which might

excite the envy of the citizens of heaven (could they ever be swayed by such a

passion), this is undoubtedly the Most Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, by means of

which men, having before their eyes, and taking into their hands the very

Creator of heaven and earth, experience, while still on earth, a certain

anticipation of heaven.

How keenly, then, must mortals strive to preserve

and protect this inestimable privilege with all due worship and reverence, and

be ever on their guard lest their negligence offend the angels who vie with them

in eager adoration!

The Mass! What a treasure! Christ's very own

sacrifice on the cross left for us wrapped in an act seeping with beauty and

divine celebration. Below I describe a few of its important qualities that set

it apart in this day and age, that truly make it "the most beautiful thing this

side of heaven".

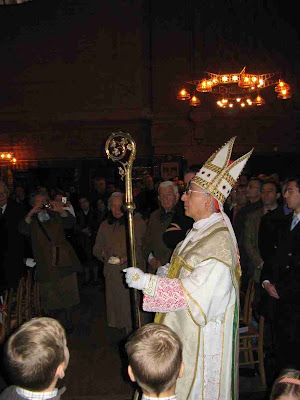

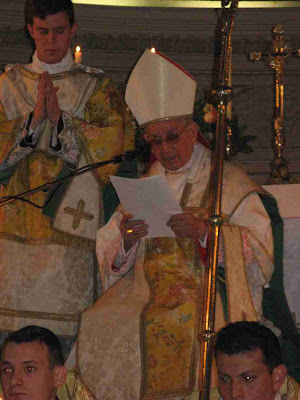

St. Mary Catholic Church,

Kalamazoo, MI

St. Mary Catholic Church,

Kalamazoo, MI

1. The Silence

of the Canon

The entire Canon of the Mass is devoid of any vocal

sounds, other than one phrase "Nobis quoque peccatoribus" where the priest

strikes his breast, emphasising his own sinfulness and unworthiness of

celebrating such an unspeakably divine action. The only other sound is when the

bell is rung, initially at the "Hanc igitur" as a warning bell to inform the

faithful of the impending consecration, and then three times at each

consecration: when the priest genuflects before the divine oblation, when he

raises the divine victim in an elevation of worship and adoration, and finally

when he genuflects again. Otherwise, complete silence.

Why this silence,

when the canon is the most important part of the Mass? Simply because of that

fact. The canon of the Mass joins the earthy sphere to the heavenly sphere.

Christ's sacrifice was performed once and for all; it can never be repeated as

it was the eternal and perfect sacrifice to end all sacrifices. However, since

the victim and the priest was God, the person of our Lord Jesus Christ, the

effects are infinite: the entire human race was redeemed wherever they lived,

regardless of time or space. But an important fact is that the act that Christ

performed was placed within His creation, and at a particular point in time.

Therefore, for the sacrifice of the cross to become effective universally over

all time, it needed to be perpetuated through the ages by a priesthood acting in

the person of our Lord and presenting His sacrifice anew to a new generation.

This is why Christ built His Church: to bring forth the graces of the

incarnation, to prolong it and "make present" its effects to all people. The

sacrifice of the cross, and the consecration in the Mass, are timeless entities

in a temporal world.

The

silence, therefore, enables us to transcend our present existence and become

present at the foot of the cross itself. Our senses, so active in the outside

world, are suppressed so that our soul can touch the divine presence of God on

the altar, so that we may be lifted up with the oblation to the altar of God

Himself in heaven, surrounded by all the Hosts and angels in constant prayer and

adoration. We, in effect, dip our toes into the pool of eternity, no longer

limited by our earthly existence in time and space, but instead become one with

our Lord in offering ourselves to God the Father in the one perfect act of

self-giving, love and adoration.

Our senses are not totally silenced

though. Through our eyes, we see the Holy Victim raises up to the Father in the

form of bread and wine; closing our eyes we see the cross above us and the

angelic party beyond. In our ears, we hear the ringing of bells, confirming what

we see and what we feel in our hearts. In our nostrils, we smell the sweet odour

of incense, floating up to heaven accompanying the Victim to the altar of God.

It is truly an entire experience of Body and Soul where the carpet of life is

swept from underneath us revealing the eternal reality of the cross and the

truth of God's love for each and everyone of us.

Using vocal words in the

canon would defy this divine reality, it would seemingly bring the events down

to a level of speech and thought, rather than action and sacrifice. We must feel

with our heart and soul the event taking place, not hear with our ears the words

which enact the event. Only silence can penetrate this mystery, with our spirit

lifting us above that temporal actions of the priest into the divine and eternal

reality of the High Priest: our Lord on the Cross.

2. The Orientation of the

Priest

Traditionally, the priest has always faced east, standing before

the altar leading the people in worship and sacrifice with Christ our Lord to

our Father in heaven. The east is where the sun rises, a symbol of the rising of

the Son of God, His glorious resurrection and the direction of His eventual

second coming. Standing before the altar, the symbol of the offering of the

sacrifice is clear to all, elevated slightly above the nave and the rest of the

sanctuary, lifting the sacrifice heavenward in an act of worship and

atonement.

St. Stanislaus Kostka

Catholic Church, Michigan City, IN

St. Stanislaus Kostka

Catholic Church, Michigan City, IN

Please

note that I do not use the terminology "facing the altar" or "facing the

people", because this inevitably confuses why the priest is standing before the

altar and not behind it. The people who are there are following the priest along

the path to eternal life. Holy Mass is not merely a meeting or an act of praise

with the presider guiding the people: it is an act of sacrificial worship and a

step to eternal life. We join the priest, who acts in "persona Christi", in

offering the sacrifice, Christ Himself, to God the Father. The entire

proceedings are a spiritual affair: we leave our worldly worries behind at the

doorway and enter a place of dimmed lights, hushed tones and reverence towards

the divine presence within. The priest leads the people in prayer and worship,

we follow as his obedient flock, as a shepherd leads his sheep to green pastures

and lush grass. It allows for intense prayer: the priest concentrates on the

offering of the sacrifice, the people concentrate on following him and lifting

their hearts up to the Father with their Lord on the cross. The interaction

between priest and the faithful is minimised so that the interaction between the

soul of each person and God is emphasised through the sacred liturgy.

3. The Prayers at the Foot of

the Altar

The job of a priest is awesome indeed. Offering any sacrifice

to God is a heavy responsibility. When the offering is also God, with God acting

through your ordained ministry, the responsibility is beyond human

comprehension. Suppose that when walking you turned a corner and met a priest

talking to an angel, who would you greet first? The angel would be constantly in

the presence of God, sinless and perfect in his praise and worship of God.

However, you should greet the priest before the angel, due to the dignity of his

vocation: in his capacity, he acts in "persona Christi" bringing forth the

graces of God's sacraments, whilst an angel merely carries messages from God, he

does not act in His place.

St. Patrick Catholic

Church, South Bend, IN

St. Patrick Catholic

Church, South Bend, IN

Due to this immense

responsibility, in the traditional Latin Mass the priest approaches the altar

with extreme care and awareness of his own unworthiness. Once the altar pieces

are in place, he positions himself at the level of the surrounding sanctuary

(normally two or three steps down from the altar itself) and starts the prayers

at the foot of the altar. These include psalm 42, which pleads for God's grace,

preparing the priest for his actions on the altar. He then, without moving

forwards, bows down low and prays the Confiteor confessing to God - thrice -

that through his own fault he has sinned exceedingly in thought, word and deed.

The server pleads to God: "May almighty God have mercy on thee and, having

forgiven thee thy sins, bring thee to life everlasting" - asking God for his

forgiveness for the poor and frail priest! The Confiteor is then repeated, this

time for the server and the faithful present, thus signifying a deep divide

between priesthood and laity. The priest continues, with the server, in asking

for God's help, and finally - after all this - ascends the steps to the altar

with the prayer:

Take away from us our iniquities, we beseech Thee, O Lord; that,

being made pure in heart we may be worthy to enter into the Holy of Holies.

Through Christ our Lord. Amen.

These proceedings reflect the

theology of the Old Testament priesthood, thus providing us with a continuation

and fulfilment of that priesthood in the person of Christ Himself, and the

priests He has since ordained.

Once the Mass is over, the priest again

bows low and offers up the following prayer:

May the lowly homage of my service be pleasing to Thee, O most holy

Trinity: and do Thou grant that the sacrifice which I, all unworthy, have

offered up in the sight of Thy majesty, may be acceptable to Thee, and, because

of Thy loving-kindness, may avail to atone to Thee for myself and for those for

whom I have offered it up. Through Christ our Lord.

Amen.

Thus the priest further emphasises his inadequacy in

offering the divine victim, recognising his human frailty before God and all

those present. For me, this is a great expression of humility before Almighty

God, who in His own infinite humility in the incarnation, instituted the

Catholic priesthood in offering up the Eucharist until the end of the

age.

4. The Use of

Latin

The

use of Latin in the Mass is very important. Firstly, it is the language of the

Roman Catholic Church. It symbolises a real and true unity across the many

countries in which the Mass is celebrated. Wherever you may enter a church in

the Latin rite, the whole proceedings will be instantly familiar to you,

bringing home an immediate feeling of the universality of the Church. The

Catholic Church is truly universal, not fixed to one country or culture, but

transcends national boundaries by simply using the same language, symbolising

its unity in faith, authority and sources of revelation.

Secondly, Latin

is a dead language. It is no longer used as a language in the streets, therefore

it has stopped evolving as vernacular languages constantly do. Due to this, the

meaning of the words has set in stone, and the liturgy does not need to be

revised to avoid offending certain people for whom the words have taken on a

different meaning. The dead language has, then, been turned into a "liturgical

language" used for the liturgical celebration of the Church. This is not

specific to the Latin rite either. The Russian Orthodox Church (although

separate from Rome) uses Church Slavonic and the Greek Orthodox Church uses

ancient Greek. When the Church was setting up in China, the missionaries there

appealed to Rome that the locals truly could not use Latin as a language since

it was so foreign to them. Subsequently, the Vatican decreed that the Church

there could use ancient Chinese that was no longer in use, thus retaining its

liturgical usage.

Thirdly, Latin exhibits a beauty and elegance that

seemingly no vernacular tongue can match. Dietrich von Hildebrand, described by

Pope Pius XII as a doctor of the 20th century Church, describes this feature as

follows:

Latin is in a unique position here. First, Latin grammar has an

uncommon clarity, and to know it, is an incomparable training for our thinking.

Secondly, Latin has a great beauty, a spiritual nobility of quite a special

sort. This is also true of medieval Latin, which moreover produced works of

highest poetical art and religious depth. One need only think of the Dies irae,

which is ascribed to Thomas of Celano, of Jacapone da Todi's Stabat mater, of

the magnificent hymns of St. Thomas Aquinas, of the sequences of Venantius

Fortunatus, and many others. The role which Latin has played in history,

especially in the liturgy, and the universality which it possesses, gives the

learning of Latin quite a special place ("The Devastated Vineyard" by Dietrich

von Hildebrand, page 90).

Latin is not a barrier, but an

invitation into the treasures of the Church, both in liturgy and music. It

cannot be seen as an obstacle to potential converts, or to the laity in general,

as the personal piety of the laity, and conversions to the Church and also to

the priesthood, were flourishing when the Latin Mass was the jewel in the

Church's crown.

5. The Gregorian

Chant

As

many popular music charts have indicated recently, the Gregorian chant appeals

to the soul now as much as ever. Its sublime effect on the proceedings of the

Mass is never to be underestimated; it truly seems to be music from heaven. St.

Gregory the Great, a Pope in the 6th/7th centuries, organised the Church music

and formally defined the Gregorian chant as it has been sung in the Church ever

since. St. Pope Pius X further reformed the music of the Church, making a

revision "not of the text but of the music. The Vatican Gradual of 1906 contains

new, or rather restored, forms of the chants sung by the celebrant, therefore to

be printed in the Missal" (according to Adrian Fortescue). Furthermore, the

Second Vatican Council stated that the Gregorian chant "should be given pride of

place in liturgical services" (Sacrosanctum concilium, 116). Mozart himself said

that "he would gladly exchange all his music for the fame of having composed the

Gregorian Preface", and Berlioz, who himself wrote a grandiose Requiem, said

that "nothing in music could be compared with the effect of the Gregorian Dies

Irae" (Latin Mass Society, newsletter no. 111, page 23).

The University of Notre

Dame, IN

The University of Notre

Dame, IN

The Gregorian chant connects with the soul, not

the mind of the believer (and non- believer alike). Without any knowledge of the

traditional Mass, people are somehow drawn towards the divine mysteries of the

Church through the treasure of the Gregorian chant. I personally was at a loss

in the first Latin Mass I ever attended - a Low Mass - but subsequently I

attended a Sung Mass with the Gregorian chant and to term a present day saying:

"I was blown away"! It has a mysterious quality that silences the senses and

speaks directly to the spirit within, connects with that ever- present desire -

however suppressed - that yearns for the "unmoved mover" Who answers all our

questions and aspirations. The chant, an expression of most religions, has

seemingly found its perfect setting in the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass - not the

concert hall or opera house - but praising the merits of our Saviour before the

Holy of Holies.

6. The Reception of

Communion

The reception of Communion within the rubrics of the

traditional Mass takes place within a sublime and prayerful world, separated

from the rushed and physical world in which we live. Again, in the traditional

Mass the physical actions of the faith are downplayed so that the spiritual

aspect of our existence can revel and take precedence.

Firstly,

the priest receives Holy Communion at a distinctly separate time apart from the

servers and laity. He recites many beautiful prayers whilst consuming the Host

and Chalice, before turning his attention to the servers and faithful present.

He does, for instance, have a separate "Lord, I am not worthy..." prayer, said

three times with the bell ringing. When he turns to the faithful, holding a

piece of the Sacred Host towards them, he says "Behold the lamb of God...", and

the faithful then recite their own "Lord, I am not worthy...", further

emphasising the different roles of priest and laity.

Secondly,

when the faithful themselves receive Communion, they receive It kneeling at the

altar rail, and directly onto their tongue. This is very significant. Receiving

Communion whilst kneeling means that the faithful line up in a row before the

sanctuary, and thus have time to prepare themselves for this most sacred of

events: coming into spiritual and substantial union with Christ Himself. The

communicant kneels down, and whilst he waits for the priest to make his way

around, he can settle himself, concentrate on the upcoming Communion with our

Lord praying intensely. When it is his turn, the priest says the prayer: "May

the body of Our Lord Jesus Christ keep your soul until life everlasting. Amen".

This means, besides the beauty and the significance of the words themselves,

that the priest says the word "Amen" so that the communicant need not invoke his

voice to receive the King of Kings, allowing a constant stream of prayer and

thanksgiving to flow from soul to Saviour. The communicant simply needs to

expose his tongue, and his side of the proceedings is complete. Upon receiving

Christ, he can continue praying for a little while, and only then does he need

to return to his seat, leaving room for the next communicant. Moreover, having

the priest come over to the communicant signifies that Christ comes to us, feeds

us with His own divine life, whilst we wait kneeling and unmoving like little

children totally dependent on His love, mercy and compassion. This is the

message of the Gospel: to become like little children, submitting our wills to

His and depending totally on Him for everything. We cannot even feed ourselves

without Christ's help, and the action of Communion in the traditional manner

demonstrates this in a very vivid manner.

Finally,

receiving Communion directly on the tongue further increases the spiritual

tranquility of the whole act. The priest, as above, performs the entire action

in dealing with the sacred Host Itself. The danger of leaving particles of the

Host on one's own hands is then avoided, as well as more worrying sacrileges

such as the Host being taken away, uneaten, dropped on the floor, or even taken

to Satanic gatherings. If a particle is left on the communicant's hand, however

small and invisible to the eye, It is still our Lord entire, Body, Blood, Soul

and Divinity. He remains fully present in the species of the Host until the Host

looses the accidents of bread. Moreover, if we are allowed to directly touch the

Blessed Sacrament, we may become casual or careless in our Lord's presence, thus

giving rise to irreverence before the great Sacrament Itself. Only allowing the

priest to touch the Host also increases our respect and reverence, not only of

the Blessed Sacrament, but of the priesthood itself and all who take it upon

themselves to enter it. The sacred Host is, after all, the very substance of God

incarnate: something that demands our extreme reverence and holy fear. To

restrict touching It to the priesthood alone can only increase these

virtues.

__________

I have covered six main qualities of the

traditional Latin Mass above which are certainly not the only ones. The whole

ethos of the Mass exhibits a profound belief in the doctrines of the one true

Church of Christ, especially in the Holy Sacrifice and the substantial presence

of our Lord, Jesus Christ. The beauty and Catholicism of the offertory prayers

confirm the doctrine of the Catholic faith in the upcoming consecration,

unambiguously. The rubrics of the Mass are very strict; when we attend a Latin

Mass we know what to expect - it depends on the Mass itself, not the

personalities that surround it. The repeated genuflections of the priest before

the sacred species confirm this most divine presence, as well as his repeated

signs of the cross over It, before and after the consecration. Before the

consecration these actions serve to bless and set the offering apart, after the

consecration to signify the reality of the cross before us and its redemptive

quality. The genuflections within the creed and the last gospel emphasise our

belief in the profound doctrine of the incarnation, the centre of the Christian

faith. The striking of the breast, during the Confiteor and the "Lord I am not

worthy..." bring in all aspects of our existence to increase our realisation of

own unworthiness and the infinite love and mercy of God.

The traditional

Mass is not something heard or listened to. It is a divine experience seeping

with the beauty of the faith, that touches the heart and soul of all who

participate, giving a boost to the spirituality of those who immerse themselves

in its mysteries. The secular world is the battleground; the Mass is the place

that charges us up, puts us in touch with our divine mission and motivates us to

face the prince of this world with great courage and faith.

I conclude by

completing the quote by Cardinal Newman, who composed the following glowing

praise for the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass, speaking by the mouth of his hero in

his book "Loss and Gain":

I declare, to me nothing is so consoling, so piercing, so thrilling,

so overcoming, as the Mass, said as it is among us. I could attend Masses

forever and not be tired. It is not a mere form of words, it is a great ACTION -

the greatest action that can be on earth. It is not the invocation merely, but,

if I dare use the word, the evocation of the Eternal. He becomes present on the

altar in flesh and blood, before Whom the angels bow and devils tremble. This is

that awful event which is the end and is the interpretation of every part of the

solemnity. Words are necessary, but as means, not as ends; they are not mere

addresses to the throne of grace, they are instruments of what is far higher, of

consecration, of sacrifice. They hurry on, as if impatient to fulfil their

mission. Quickly they go - the whole is quick; for they are all parts of one

integral action. Quickly they pass, for the Lord Jesus goes with them, as He

passed along the lake in the days of His flesh, quickly calling first one and

then another. Quickly they pass, because as the lightning which shineth from one

part of the heaven unto the other, so is the coming of the Son of man. Quickly

they pass; for they are as the words of Moses, when the Lord came down in the

cloud, calling on the name of the Lord as He passed by: 'The Lord, the Lord God,

merciful and gracious, long-suffering and abundant in goodness and truth.' And

as Moses on the mountain, so we, too, 'make haste and bow our heads to the

earth, and adore.' So we, all around, each in his place, looking out for the

great Advent, 'waiting for the moving of the water,' each in his place, with his

own heart, with his own wants, with his own thoughts, with his own intentions,

with his own prayers, separate but concordant, watching what is going on,

watching its progress, uniting in its consummation; not painfully and hopelessly

following a hard form of prayer from beginning to end, but like a concert of

musical instruments, each differing but concurring in a sweet harmony, we take

our part with God's priest, supporting him, yet guided by him. There are little

children there, and old men, and simple laborers, and students in seminaries,

priests preparing for Mass, priests making their thanksgiving; there are

innocent maidens, and there are penitent sinners; but out of these many minds

rises one eucharistic hymn, and the great Action is the measure and the scope of

it.

source

source

In the Liturgy the Sense of Catholicity and Unity

C: One or two have difficulties, but those are a few exceptions, because most agree with the Pope. Rather, we find expressed some practical difficulties. We need to be clear: this is not a return to the past but a step forward, because this way you have two treasures, rather than only one. This treasure, therefore, is being offered, respecting the rights of those who are particularly attached to the old liturgy. There then may follow some problems to be solved with common sense. For instance, it can happen that a priest does not have the appropriate preparation and cultural sensitivity. Only think of priests that come from areas where the language is very different from Latin. But this does still not mean a rejection: it is the presentation of a real difficulty, which is to be surmounted.

C: The excommunication concerns only the four bishops, because they have been ordained without the mandate of the Pope and against his will, while the priests are only suspended. The Mass they celebrate is without a doubt valid, but not licit and, therefore, participation is not recommended, unless on a Sunday there should be no other possibilities. Certainly neither the priests, nor the faithful are excommunicated. Let me reiterate in this regard the importance of a clear understanding of things to be able to judge correctly.

http://accionliturgica.blogspot.com/

http://accionliturgica.blogspot.com/